GROUNDBREAKERS

By | Spring 2023

Mendoza’s Ph.D. programs open a new epoch as the College seeks to nurture a distinctly Notre Dame business research culture.

In the field of medicine, researchers know that new knowledge drives better care for patients.

In the field of medicine, researchers know that new knowledge drives better care for patients.

In 1950, medical knowledge was expanding faster than ever. It was set to double in 50 years’ time. But as the century progressed, the pace of discovery accelerated. Today, according to some estimates, medical knowledge doubles in a dizzyingly fast 73 days.

But as you might expect, this explosion in knowledge does not always lead to better care. As Peter Densen, M.D., puts it, “Knowledge is expanding faster than our ability to assimilate and apply it effectively.” A new procedure, medicine or diagnostic technique discovered today will still take an estimated average of 17 years to become common practice in hospitals.

But not all hospitals are the same, as Jason A. Colquitt, Franklin D. Schurz Professor of Management at Mendoza College of Business, points out. Some hospitals have a special advantage — namely, those that are connected to medical schools.

“Who would you rather have perform your surgery?” he asks, “A doctor whose knowledge is based on what textbooks said a decade ago, or a doctor who is actively involved in research projects, who is up to date with the latest findings, and is even working to train doctors to enter the field?”

For Colquitt, who directs Mendoza’s new Ph.D. in Management, this underlying principle guides the new program.

“When you’re in a teaching hospital, medical students are seeing you alongside some of the best doctor instructors in the country. It’s going to be much the same for us. Our students will teach and conduct research in the College, and we will be alongside them, preparing them, assisting them and everyone will benefit. When students read from a textbook, they hear about research from five or 10 years ago. When they hear from researchers, they hear about what is happening now.”

Assembling the Pieces

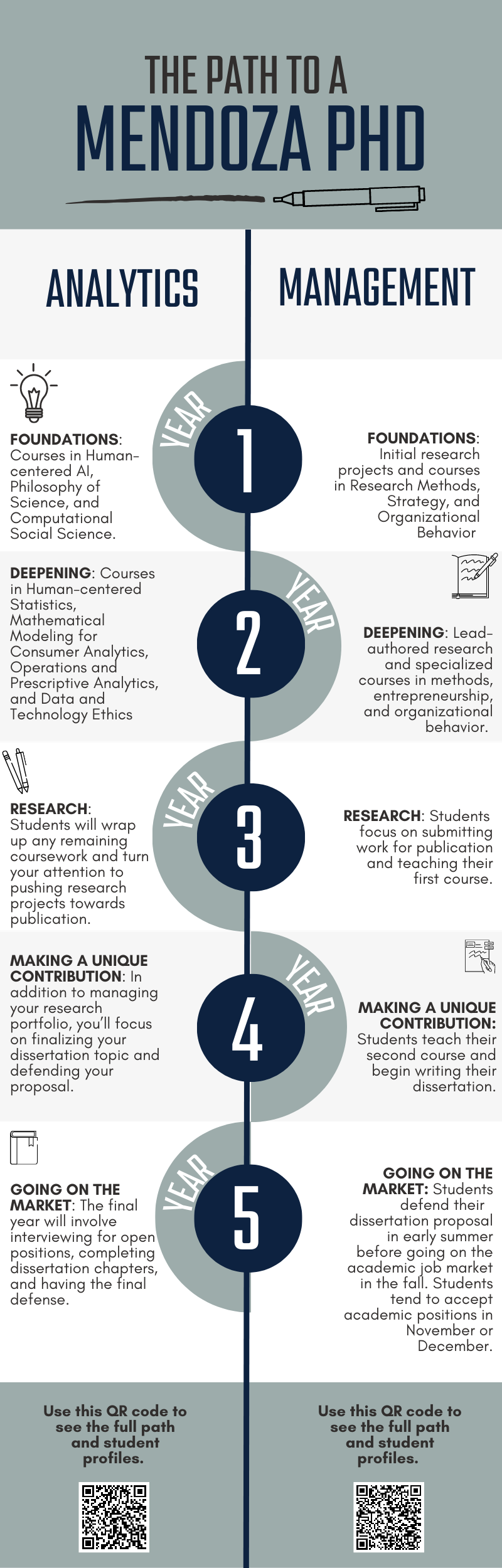

Mendoza’s first-ever Ph.D. programs — one in Management and one in Analytics —

Mendoza’s first-ever Ph.D. programs — one in Management and one in Analytics —

received their official approval from the Notre Dame academic council during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when the need to rapidly apply new findings — not just in medicine but also in business — became especially evident. But the idea for a Ph.D. program was not a new one. In fact, conversations about the need for a doctoral program within the College date back at least half a century.

Some of the earliest conversations took place in the 1970s. Eventually, in the 1990s, then-dean Jack Keane officially integrated a program into the College’s strategic plan. But as many found out, a truly excellent Ph.D. program has a clock-like complexity. It can be difficult to get all the pieces working together. It requires the right mix of opportunities to teach, conduct research, collaborate, publish and attend conferences. And it all has to run in smooth succession as students progress semester after semester on their way to becoming respected members of the field.

The idea stalled as faculty and administrators worried that a Ph.D. program would not match the size of the College’s ambition for it. If it could not be excellent, they concluded, it was better for it not to exist at all.

In the past five years, many of those pieces did finally fit into place. Senior scholars such as Colquitt arrived. They brought with them a wealth of experience in mentoring Ph.D. students and pioneering breakthroughs in business research. Most importantly, many had experience as editors of the leading scholarly journals that publish business research.

“Our claim is that we can teach students how to do impactful research. And we can back that up by showing we’ve been an editor or an editorial board member in the field’s best journals,” Colquitt explains. “When you have been a gatekeeper and a lifeguard for other people’s research projects, you understand what it takes to do research that gets published and changes the field.”

The College also decided to ensure excellence by starting small. Rather than a single college-wide doctorate in business, Mendoza launched two highly focused programs — one in management and one in analytics. After the initial cohort of four in each program, the programs will only admit two or three students each year to ensure that each one receives a multitude of opportunities to succeed.

Although the programs launched in the fall of 2022, the College has already begun to notice benefits. “We have already seen it help with recruiting new faculty,” Colquitt says. “The best faculty want to be part of a vibrant research culture. We were missing a link before, and now it is in place.”

Finding a Voice

In addition to a “vibrant” research culture, Colquitt says that the effort to build a better business researcher at Mendoza will also have a distinctive Notre Dame stamp.

“This is a very special place,” he says. “Notre Dame values will be a big part of this program, and the two main ways both have to do with ethics.”

The first is the ethics of research. Colquitt points to the struggles with replication in organizational psychology and related fields. When published results have failed to replicate in later studies, some studies have had to be retracted and some faculty — even some at leading institutions — have been found guilty of falsifying data.

Secondly, Colquitt points to the need for more research on ethical business practices. “One of the most vibrant areas of research in management as a field right now is diversity, equity and inclusion,” Colquitt says. “And there are other related areas like economic inequality, the meaning of work and employee well-being — those are the things that our mission to ‘Grow the Good in Business’ is constantly leading us back to.”

While students will be grafted into the ongoing work of Notre Dame and its faculty members, they will also benefit from mentorships that help them develop their own distinctive voice as a researcher.

“It’s what the academic job market demands these days. To get a job at a top business school, you need your own brand,” says Colquitt.

When Colquitt thinks about mentorship, he points to his own experience as an undergraduate researcher writing a senior thesis. He had just the seed of an idea: What happens when team leaders fail to act on the suggestions their followers bring forward? He thought the idea was an idea about brainstorming. A senior faculty member with whom Colquitt met offered a different perspective: “This isn’t an idea about brainstorming,” he said, “It is an idea about justice.” This suggestion helped Colquitt’s seed of an idea grow and branch into related areas of scholarship. Colquitt became a leading scholar of organizational justice, and went on to develop one of the most influential and widely used measures of the phenomenon.

Colquitt puts this kind of mentoring at the heart of Mendoza’s program. For him, this makes the program stand out within the larger landscape of graduate business programs.

“In the Ivy League,” he says, “you often see an ‘entrepreneurial’ model — which is sometimes code for, ‘We’re going to leave you alone and not mentor you.’” The other model, more typical of large public universities, he says, is “the apprenticeship model,” which is centered on “hands-on instruction working side-by-side with faculty.”

Colquitt says, “At Notre Dame, we can combine the best of both models. We — the faculty — are going to work as hard to train you as any public school. But in the end, you’re coming out with a Notre Dame degree. It’s that status and those values that you bring with you into the world.”

This distinctive model is built into the way a student progresses through the program. During their first year, students focus on learning hard research skills by joining faculty research projects such as Colquitt’s current organizational justice projects. Once they enter the second year, students will begin to find their own voice.

“Hiring committees need to view students as doing their own work and not just their advisor’s,” Colquitt says. “In addition to that, we want students to work on what they are passionate about. Some other schools leave that for the dissertation, which is much too late to develop an identity.”

The Old and the New

The new Ph.D. program in Analytics launched at the same time as the Ph.D. in Management, but it is new in another respect as well: It is offered by Mendoza’s newest department — Information Technology, Analytics, and Operations.

When its director, Ahmed Abbasi, speaks about the program, he does not start with the “new,” but with the old. Abbasi, who is the Joe and Jane Giovanini Professor of IT, Analytics, and Operations, speaks not about the latest technical skills students will learn but about leadership.

When its director, Ahmed Abbasi, speaks about the program, he does not start with the “new,” but with the old. Abbasi, who is the Joe and Jane Giovanini Professor of IT, Analytics, and Operations, speaks not about the latest technical skills students will learn but about leadership.

“We want to produce a certain type of leader,” says Abassi, who also is the co-director for Mendoza’s Human-centered Analytics Lab (HAL), “Leaders in business and in society. World leaders, managers, thought leaders who are ethical, who focus on impact. They don’t just focus on monetary outcomes but on the outcomes to human beings and their lives. That is what the Notre Dame mission has always emphasized.”

Abbasi says the key is to help students have the values and capabilities to hang onto what is most significant in the confusing environment of a data-enabled world.

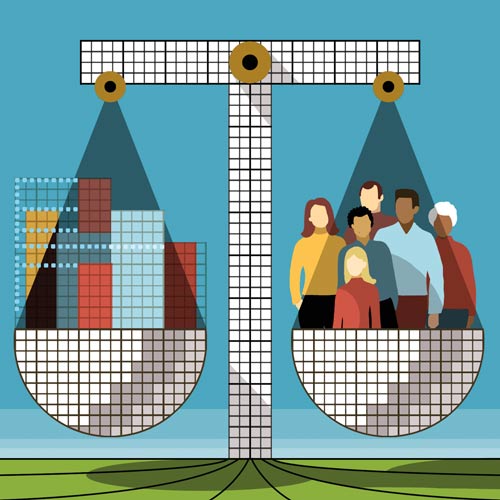

“Data is the new currency of decision making. But how do we make ethical, human-centered decisions?” he says. “We need ethical, human-centered analytics. This is one of the grand societal challenges for the next 50 years. There is so much complexity in data analytics, in machine learning and in econometrics. A lot of business schools are producing students that are really strong in those methods, who can answer ‘Could we?’ questions. Our students will be strong in that, too. But they will also know how to ask the larger ‘Should we?’ questions, the questions about purpose and impact.”

When Abbasi speaks about the difference between “Could we?” and “Should we?” questions, he is speaking from experience.

When he was in business school 20 years ago, he worked in an artificial intelligence lab. “It was all about the art of the possible,” he says.

Abbasi worked on crime analytics. He used data sets about past crimes to predict who might commit a crime, who is likely to be a repeat offender or who should get parole. He likens it to the Tom Cruise movie Minority Report, in which a set of savants with psychic powers predict crimes. Or, rather, they mispredict them. Today, Abbasi realizes that just like the fictional psychics in Minority Report, the advanced models he was using then had a wide array of blind spots and limitations.

“Today, we recognize that a lot of these models have problems. They have the positive aim of stopping crime. But bias can creep into the datasets, and there are unintended consequences if you make an error about something so important.”

Abbasi’s research now focuses a great deal on the ethical and unethical dimensions of emerging technologies. Algorithmic bias and fairness crop up every day in companies, he says.

“What if companies use people’s videos and images to score their personalities or quantify their attractiveness so we can better understand hiring and career trajectories?” he asks. “Is that something we should be doing?”

He mentions also the area of privacy as an example of an ethical issue all analytics Ph.D. students are attuned to. “At its core, analytics is about deriving insight and foresight from data. How do you monetize data?” he says. “There is this natural tension that the more data you have, the better job you can do with those insights and foresight. So privacy becomes a big challenge. Just because we can, just because it is technically doable, doesn’t mean it is right.”

Abbasi admits to not having all of the answers, but he insists that the debates themselves are what matter most. “We weren’t talking about these things 20 years ago,” he says.

Prepared to a ‘T’

While Abbasi does not have the answer to every ethical issue, he does have an answer about what kind of person is the best to encounter these problems: a “T-shaped” person.

Here, “T” refers to a person with deep technical expertise — the vertical line. But it also refers to a person who has broad knowledge and understands the larger context in which to place problems, including how to talk to a broad range of other professionals with their own technical skill sets.

“Sometimes you lose that human side,” he says. “We frame problems abstractly and we lose the ethical dimensions of what we are doing. So our program wants to produce efficient scholars that are not only focused on the ability in methods but are also able to frame research problems so they understand the impact on society.”

“Sometimes you lose that human side,” he says. “We frame problems abstractly and we lose the ethical dimensions of what we are doing. So our program wants to produce efficient scholars that are not only focused on the ability in methods but are also able to frame research problems so they understand the impact on society.”

To build the top of the T, the program includes coursework on how to translate analysis into narratives that are meaningful to other people.

“Business schools in general have a significant role to play in making sure we maintain some semblance of a moral compass as a society.”

“There are only two options,” Abbasi says, “Ethics by design or ethics as an afterthought. And when it is an afterthought, you are going to have a patchwork approach to it.”

Recently, Abbasi wrote an article arguing in favor of a “fairness by design” approach to machine learning. Pointing to recent examples of “machine learning gone wrong” in which algorithms perpetuated biases or caused harm, Abbasi made a few practical suggestions. He and his collaborators argued that data scientists need to work closely with social scientists, that machine learning should include measures of fairness, and that data sets should not cause bias by misrepresenting the populations they will be used to influence.

The phrase “by design” is now core to the Ph.D. in Analytics approach.

In much of the published research in the field of analytics, Abbasi says, concerns about ethics are so much an afterthought that they literally come at the end of a research paper.

“Scholars might include a section on the limitations of their findings, saying something like, ‘We also need to think about the consequences of doing this ...’ he says. “But we want to go a step beyond that. The broader concerns about the impact on society are everywhere — in the curriculum and the program and the students and the faculty we recruit.”

Branching Out

Both Abbasi and Colquitt admit that one of the toughest things about launching the programs is waiting to see the long-term results. It is like planting a seed, watering it and caring for it for years as it grows, they say. The students who entered the program this year likely will not enter the job market until the beginning of their fifth year in the program. All of their publications, discoveries and teaching opportunities still lie in the future.

Even then, the students will not have a direct impact on Mendoza because the widely accepted practice in doctoral studies is that universities granting doctorates do not hire their own students as professors.

“The aim is for them to move elsewhere,” Abbasi says, “And they know that going in. Our students are not going to be professors at Mendoza after they graduate.”

But it is in this very fact of “branching out” that Abbasi and Colquitt locate the long term vision for the Ph.D. program.

“What we’re doing,” Abbasi says, “is changing the ecosystem of ideas by planting a sort of academic family tree with professors who share our view of the world and bring that view elsewhere. Many of the most well known doctoral programs — like the University of Michigan, for example — have an academic family tree that focuses on a certain perspective and certain types of research. If you want your ideas to get traction and you want to create new paths for research that align with your kind of value system and your mission, that’s what you have to do.”

Colquitt expands on Abbasi’s ecological metaphor, saying, “Colleges like Mendoza hire from the ecosystem every year. But there’s something not quite right about taking from the ecosystem and not giving back to it — particularly because we have so much to offer. What we will start to do now is give back to the ecosystem. Now we hire two to four Ph.D.s in a given year from other places. We’re going to supply that same number of Ph.D.s, at least in management. A give and take is always an important part of science.”

He says this offers a wholly new way of thinking about Mendoza’s mission to “Grow the Good in Business.”

“Over the long term,” Colquitt says, “our mission will not just be about what we can produce here, but also what we produce elsewhere. Imagine 10 or 20 or 30 years down the road: Mendoza Ph.D.s teaching at other business schools. Picture walking down the hallways of NYU and USC and WashU and Michigan, and there are our Ph.D.s teaching those classes. I think that’s a vision we should get behind, and that is our long term goal.”

Meet the first Ph.D. cohort here.

Illustrations by Pierluigi Longo.

Comments