ON READING THE BIBLE

By | Spring 2019

Some years ago, a first-year student came by my office asking to be exempted from the first obligatory theology course, which centered on biblical studies. She explained that she already had read the Bible in high school. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry, but I refused the exemption. My educated guess, I told her, was that she would in fact learn a thing or two.

Without a doubt, it’s useful to read the Bible, whether out of curiosity, for pious reasons or mere information. But there is a broader reason than either as an individual reading on his or her own, or in a congregational setting led by a lector.

The Bible also is a resource for morality. Its text is performed in ritual in baptism, the Eucharist, ordination and other sacraments. It is reframed as a source for formal prayers such as the Psalms, the “Our Father” or the first half of the “Hail Mary.” Furthermore, the Bible is read in community in order to formulate the fundamental teachings of Christianity. The creed, after all, is merely a synopsis of what the biblical tradition affirms.

Over the decades, it has been a custom of mine to write out texts from Scripture in my reading notebooks because those texts seem to me to be saturated in meaning. They are classic texts in the sense that they possess an overflow of meaning that points beyond the first meaning of the text. What is true of texts is equally true of words in the Bible.

Over the decades, it has been a custom of mine to write out texts from Scripture in my reading notebooks because those texts seem to me to be saturated in meaning. They are classic texts in the sense that they possess an overflow of meaning that points beyond the first meaning of the text. What is true of texts is equally true of words in the Bible.

Karl Rahner, the famous German theologian, calls them Urwortes — primordial words (like bread or heart or grace) that overflow with meaning. The entire Christian tradition from the earliest Christian writers to contemporary preachers and theologians reach up to those words attempting to plumb their depth.

Biblical language at its best expresses more than we can say, offering us a richness that nourishes our faith. I could offer thousands of examples to make this point, but let me offer just one. In the famous fourth chapter of Paul’s letter to the Galatians, the apostle prefaces his point that we are by adoption what Christ was by nature — a Son — to begins with this brief clause: “In the fullness of time, God sent His son, born of a woman, born under the law...” (Galatians 4:4). Let us think of that affirmation.

In the fullness of time. Paul does not say “once upon a time” or “way back when.” He refers to when time had reached that certain maturity, wishing us to think about the sacred history of the Jewish people whose history is recorded in the Bible. In other words, the way to understand the unfolding of time is to understand it as the unfolding of history, not the accumulation of myth.

God sent His Son. Divinity entered history at a precise time — when it was “full” — which is another way of saying what John in his prologue says: The Word became flesh and dwelt among us. To say it differently: We do not reach up to God, but rather God came to us in the person of His Son.

Born of a woman. This is the only place in Paul’s letters where he speaks of Mary, but he does so to make a precise point, namely, that Jesus was a true human being and not an angel or a wraith or a pure spirit. He was a man who, as it is said elsewhere, is like us in all things except sin.

Born under the law. Paul furthers denies that Jesus was some generic ideal type of human being. He was born in time as a Jew — born into the covenant world of Torah. The profound lesson here is that any reflexive anti-Semitism fully contradicts the claims we make of Jesus. Paul wants us to think of Jesus as a true human man born in time as a Jew.

When I first wrote that text from Galatians into my reading notebook, I thought to myself that one could tease out the implications of those four little affirmations and end up writing a huge book about the nature of time, history, incarnation and the unity of biblical witness. I never wrote such a book nor was I tempted to do so. But still, I do not think I have fully grasped what those four affirmations mean.

Years ago, the great Canadian literary critic Northrup Frye remarked in his book, “The Great Code,” that the Bible is endlessly self-referential because what one reads in one place must be read in the light of what has been already said and what may be said ahead. When Jesus called himself the Bread of Life, one must read that back against the saving manna in the desert and forward to the Last Supper and the Eucharist.

This is what I hoped the young woman who was in my office that day would come to understand, but I do not know if that in fact is what happened. If she did begin to see such richness, she would also learn another truth: When we fully engage the Scriptures, we not only read them but they begin to read us.

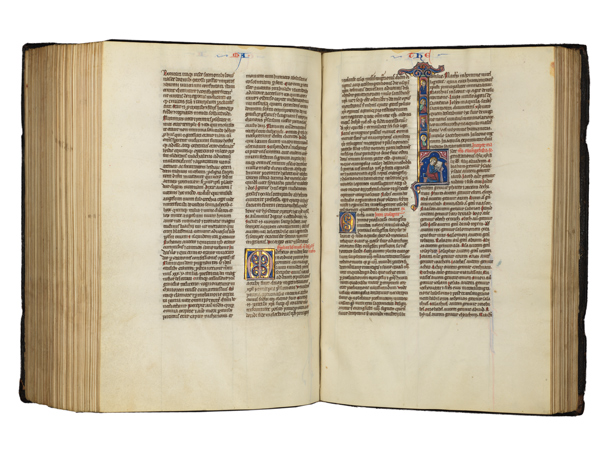

THE FERRELL BIBLE (pictured)

The Ferrell Bible (Ferrell MS 1), donated by James and Elizabeth Ferrell is an illustrious example of the historiated Bibles produced during the 13th century. These Bibles were renowned for their fine artistry, innovative techniques and intricate detail.

Lawrence S. Cunningham is the John A. O’Brien Professor of Theology Emeritus at the University of Notre Dame.

Lawrence S. Cunningham is the John A. O’Brien Professor of Theology Emeritus at the University of Notre Dame.

Comments